ONTARIO — The smell of dog urine permeated the seats of Linda Talbott’s white Ford Escape.

It was October. The air was chilly. The car was the only shelter she had left, but Talbott could hardly bring herself to get back in.

She had been living in the parking lot of the Ontario Walmart for almost a month. Every time she had to use the restroom, she endured the long walk across the parking lot and judgmental stares of superstore patrons.

It had been weeks since she’d enjoyed heat, a shower or a fresh change of clothes. Her car wouldn’t start. Her phone was dead. Her two little dogs had urinated all over her belongings, but she couldn’t bring herself to give them up; Ray Ray and Darla were the only family she had left.

For decades, Talbott lived a typical life. She had a job, a husband, a home and friends at the local community center.

Then she met a man online. He convinced Talbott, a 71-year-old widow, that he was in love with her.

He said his name was James.

Over the course of nearly two years, Talbott built an online relationship with someone she thought she could trust. Instead, Talbott said “James” scammed her out of nearly $12,000 — a loss that eventually lead to her living in her car.

An online romance led to living in her car

It began with a friendship, or at least it seemed that way.

“It just started talking about things we liked, didn’t like,” Talbott said. “He asked me what I was looking for in a man and then that just escalated from that.”

James asked Talbott about her family (she didn’t have any). He called her baby. He told her he loved her.

“He said he lived in San Diego, California and he was two years younger than me,” she recalled. “He was going to come to Mansfield so we could get married.”

Eventually, James talked Talbott into handing over her Social Security number. Soon, her Social Security checks were being routed to a bank in Birmingham, Ala. He also tricked her into cashing a fraudulent check, which left her on the hook for $5,000.

“He preyed on her. He made sure she did not have anyone,” said Michelle Bollinger, a friend of Talbott’s. “He kept calling it ‘their money.’”

Meanwhile, James continued to promise a wonderful life together. He painted a picture of the two of them on a family ranch in Texas.

When Talbott’s relationship with her female roommate soured, she thought she’d have him to fall back on.

“I talked about this guy I met online, and she says, ‘Well, if you’re gonna get married again, just move out,’” Talbott recalled. “So I did.”

That’s how she ended up living in her car. She drove back and forth between the Walmart and JoAnn Fabrics parking lots for a few days before her car battery died, leaving her stranded.

Even when Talbott’s situation grew dire, the scammer continued to target her.

“It just made me sick to read the messages,” Bollinger said. “He knew that she was living in her car. He did not care.”

That’s when Talbott realized James wasn’t who he said he was. But by then, it was too late.

“They can tell you anything to get you to believe them,” Talbott said. “He didn’t care that I was homeless.”

Romance scams cost Americans millions each year

Experts on fraud say stories like Talbott’s are all too common.

The Federal Trade Commission received more than 269,000 reports of romance scams between 2019 and 2023, with total reported losses of $4.5 billion dollars.

Romance scams often follow a typical playbook: An attractive stranger with a fake name and profile photo reaches out online and strikes up a connection. They build up a sense of trust. They send messages daily.

They declare their love but never show their face. They talk about building a life together, but say it will have to wait. They’re in the military, living overseas or working on an offshore oil rig.

They may invite their target to communicate using a less-secure platform like a chat room, email or text messaging app.

Sometimes, scammers pose not as a romantic partner, but a new friend.

“They’ll talk with them. They’ll create a backstory. Sometimes it’s sympathy… I have kids and I need help to be able to take care of my kids,” said Richard Meeks, who supervises Adult Protective Services in Knox, Wyandot, Crawford and Marion counties.

Inevitably, the stranger ends up in dire situation. They need money — typically in the form of cryptocurrency, a wire transfer or gift card redemption codes.

Meeks said he’s seen an uptick in elder exploitation as more senior citizens struggle with solitary lifestyles.

“A lot of times (victims) are those people who are isolated, lonely, and now this person is making them feel special and important.”

Some scammers even steal funds by offering to help the victim — all they need is the victim’s bank account information and they’ll send a deposit.

Know the warning signs of a romance or relationship scam

Romance scams often begin with unsolicited message on social media or a dating platform. If you choose to communicate with strangers online, be aware of the following warning signs that may point to trouble:

- They claim to want to meet you, but can’t because they are living or working far away

- They pressures you to act quickly

- They ask you to send them money via cryptocurrency, wire transfer or gift card codes

- They offer details about their life that are vague or inconsistent

- They seek personal information like Social Security number, bank account information, credit card numbers, home addresses, date of birth or mother’s maiden name

- They claim to be sending you a gift, but need money for delivery or customs fees

- They offer to help you invest in cryptocurrency

- They provide vague or inconsistent details about their personal life

- They request sexually explicit photos or videos

- They ask you to communicate on a different website or via text or email

- They become defensive or angry when you question their intentions

- They encourage you to keep your relationship a secret or lie to family, friends and financial institutions

Victoria Hicks, a navigator supervisor with the Area Agency on Aging, said she recently met an individual who communicated with an online scammer for six months before their bank account was emptied.

“They were like, ‘But I don’t understand, this was my friend. I talked to this person every day.’” Hicks said.

“You think you know someone that you’ve talked to every day for six months. You don’t. (The scammer) wasn’t even in the country.”

Viral Facebook post helped get Talbott back on her feet

As a former prison guard, Michelle Bollinger learned to be aware of her surroundings.

That may be why she noticed the SUV sitting in the far corner of the Walmart parking lot.

It had been parked there for days, maybe weeks. She kept an eye on it. Was it broken down? Abandoned?

When Bollinger finally decided to approach the vehicle on a Friday afternoon, she saw two small dogs — but no owner.

Then, an elderly woman with gray hair and glasses appeared, leaning on an empty shopping cart for support as she hobbled toward the car.

Bollinger looked at Talbott and saw glimpses of herself. On top of it all, she looked to be about her mother’s age.

“I asked her if she was okay, and she kind of hung her head and said she was homeless,” Bollinger said.

“I’ve had to sleep in my car before, though not for a long period of time like her,” Bollinger added. “Nobody should have to live like that.”

Bollinger drove to the Area Agency on Aging. Bollinger said a staff member made a report to Adult Protective Services and told her someone would be out to check on Talbott.

Frustrated by the lack of an immediate response, Bollinger asked if she could take Talbott’s picture and post it on social media. She hoped it would “light a fire” under someone who could help.

Talbott agreed. She took Ray Ray and Darla in her arms and smiled like nothing was wrong.

The response was immediate.

“I was not prepared for what happened next. It was quite overwhelming,” Bollinger said. “The response I got was just crazy. It had taken off like wildfire.”

Bollinger was bombarded with messages offering to donate cash and necessities. She took time off work to respond to them all. Uncomfortable with handling funds on Talbott’s behalf, she set up a GoFundMe. It raised $3,000.

Talbott used the funds to get caught up on car payments and auto insurance. She purchased some groceries and new clothes.

Meanwhile, the Area Agency on Aging set Talbott up in a hotel and assigned her a caseworker.

In early November, her hotel stay ended, but she had nowhere to go.

Bollinger offered her a spare bedroom. The Area Agency on Aging provided funds for a mattress.

Bollinger and Talbott’s case worker helped her set up a new bank account and get her Social Security checks sent to her.

With a safe place to live, Talbott resumed her medical and mental health care. She began crocheting again — something that’s helped her cope with depression over the years.

Age, trauma and loneliness can increase vulnerability to scams

While anyone can be victimized by a scam, several factors may make certain individuals more vulnerable.

Meeks said unresolved trauma from hardships like child abuse, a painful divorce or an abusive relationship can make individuals more susceptible. Those who don’t find healthy ways to cope and process their pain may seek validation from relationships, which can lead them to ignore red flags.

Talbott had certainly experienced her share of hardship. She was adopted as a toddler due to her mother’s neglect and substance abuse. She was recently widowed and had no children. Her marriage had been an unhappy one.

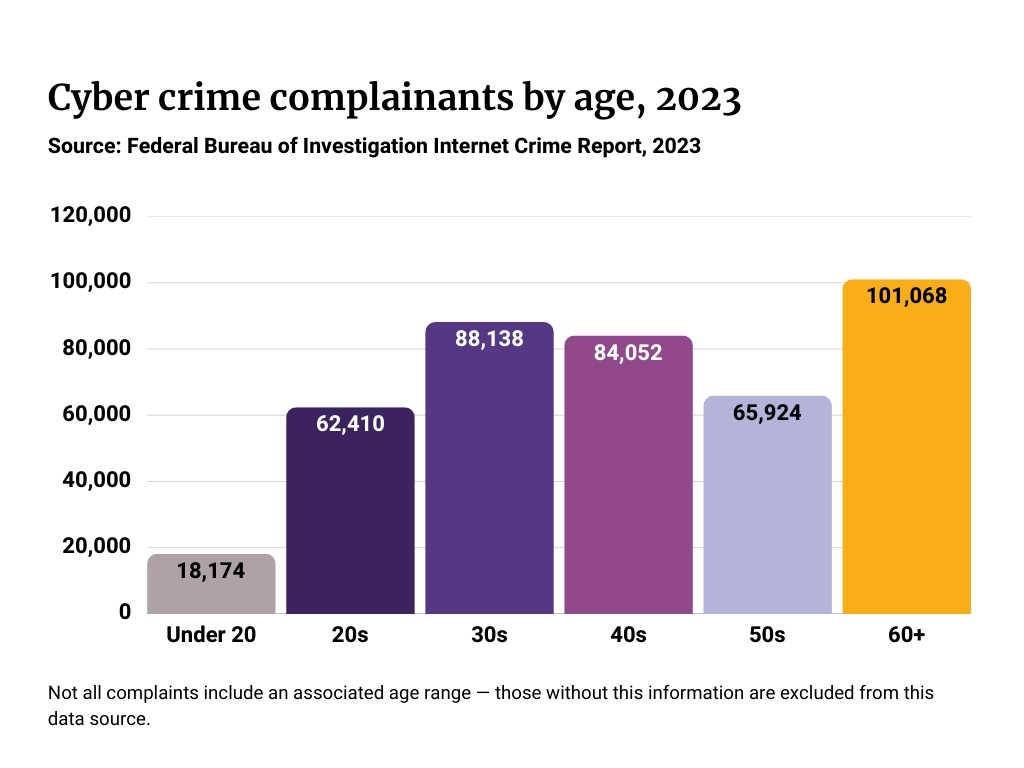

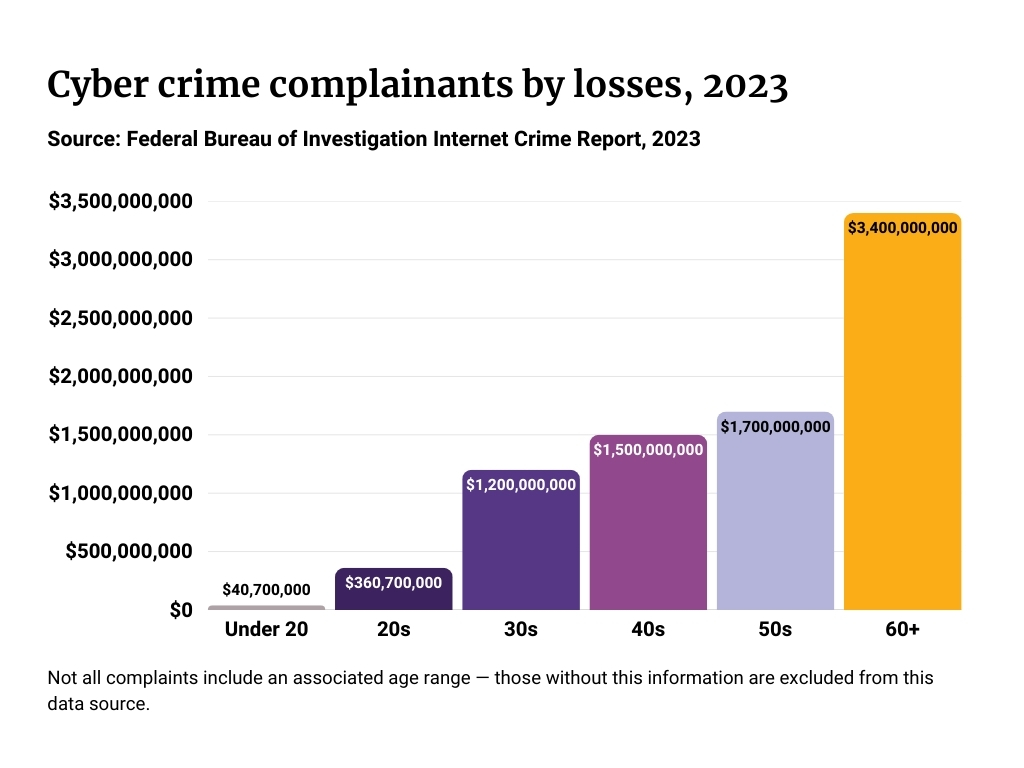

Older people are disproportionately impacted by financial fraud, according to the FBI. Seniors are often targeted because they tend to be trusting, polite and have assets like homes and financial savings younger generations don’t.

Elder fraud complaints to the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (or IC3) went up by 14 percent in 2023, while financial losses increased by about 11 percent, according to the FBI’s 2023 Elder Fraud Report. Scams targeting individuals aged 60 and older caused over $3.4 billion in losses in 2023, with an average loss of $33,915.

Nevertheless, experts say anyone can fall victim to fraud and exploitation, regardless of their age, circumstances or status.

The FBI’s 2023 Internet Crime Report states that different age groups tend to be impacted by different types of crimes. For example, victims between 30 to 49 years old were the most likely group to report losses from investment fraud, while the elderly accounted for more than half of financial losses to tech support scams.

There are several factors that make addressing fraud challenging, especially with older victims.

Sometimes, a victim is unable to recognize the person scamming them isn’t who they say they are. Agencies like Adult Protective Services, the Area Agency on Aging and law enforcement can offer assistance — but they can’t force scam victims to accept it.

“Some people, they become convinced it’s real, and it becomes very difficult in those cases to be able to assist,” Meeks said.

Other victims may hesitate to come forward because they feel ashamed. Older victims often fear they’ll be deemed unfit to manage their affairs.

“I think that is a huge barrier for a lot of people — that fear that people are going to see me as lesser because of this,” Hicks said.

That embarrassment may lead to further isolation, making a scam victim that much more vulnerable to re-victimization.

“When you look at the statistics, there is a high percentage of individuals that will be scammed again,” Meeks said.

“It becomes a cycle, because sometimes they’ve gone through hurt and pain. Well, what do I do when I go through hurt and pain? I look for validation. I look for somebody to reach out to, for social support.”

That’s why experts say said it’s important to erase the stigma around financial exploitation and support victims as they recover financially and emotionally.

“We encourage family friends to rally around, support, be non-judgmental, to be able to help and assist them, so that doesn’t happen again,” Hicks said.

Meeks encouraged scam victims to change their phone number, email address and other online contact information.

“Now your information is out there on the dark web and unfortunately, somebody else is going to follow up, because they know you’ve been susceptible,” he said.

In February, Talbott moved into her own apartment. Her scammer remains at large.

“He’s probably mad he’s not getting my money any more,” Talbott said. “But I need it more than he does. Things ain’t cheap.”

Looking back, Talbott said she shouldn’t have given out her financial information, but she wants to share her story as a warning to others.

“I know I did wrong,” she said. “I just don’t want somebody else to get hurt.

“I recommend anybody that starts talking to somebody (online), just delete them. It ain’t worth it.”

Click Here For The Original Source.